The Hardships with 65 Years of Self-Advocating

A Disabilities Advocate Reflects on His Life

During the later years of the 1970s, Bill Byrne enjoyed walking his dog down the road in his town of Barrington New Jersey as he does every week. When the weather was warm, the two of them would explore the quiet neighborhood. When the weather was cold, Bill dressed warm and wore gloves that wrapped around the leash, making sure not to walk too far.

Turning around the corner, Bill ran into a group of kids from grammar school he didn’t know. “Hey retard, if you’re so strong, pick up this,” they say to Bill as they spit on the ground.

As they point and laugh, Bill runs home crying with his dog trailing behind, as he does almost every week. He tells his dad he can’t take it anymore, that every time he walks down the street, someone makes fun of him. His dad takes time to calm him down, telling Bill it isn’t his fault.

“Next time they make fun of you, say Jesus loves you,” his dad tells him. After that the kids started to walk away.

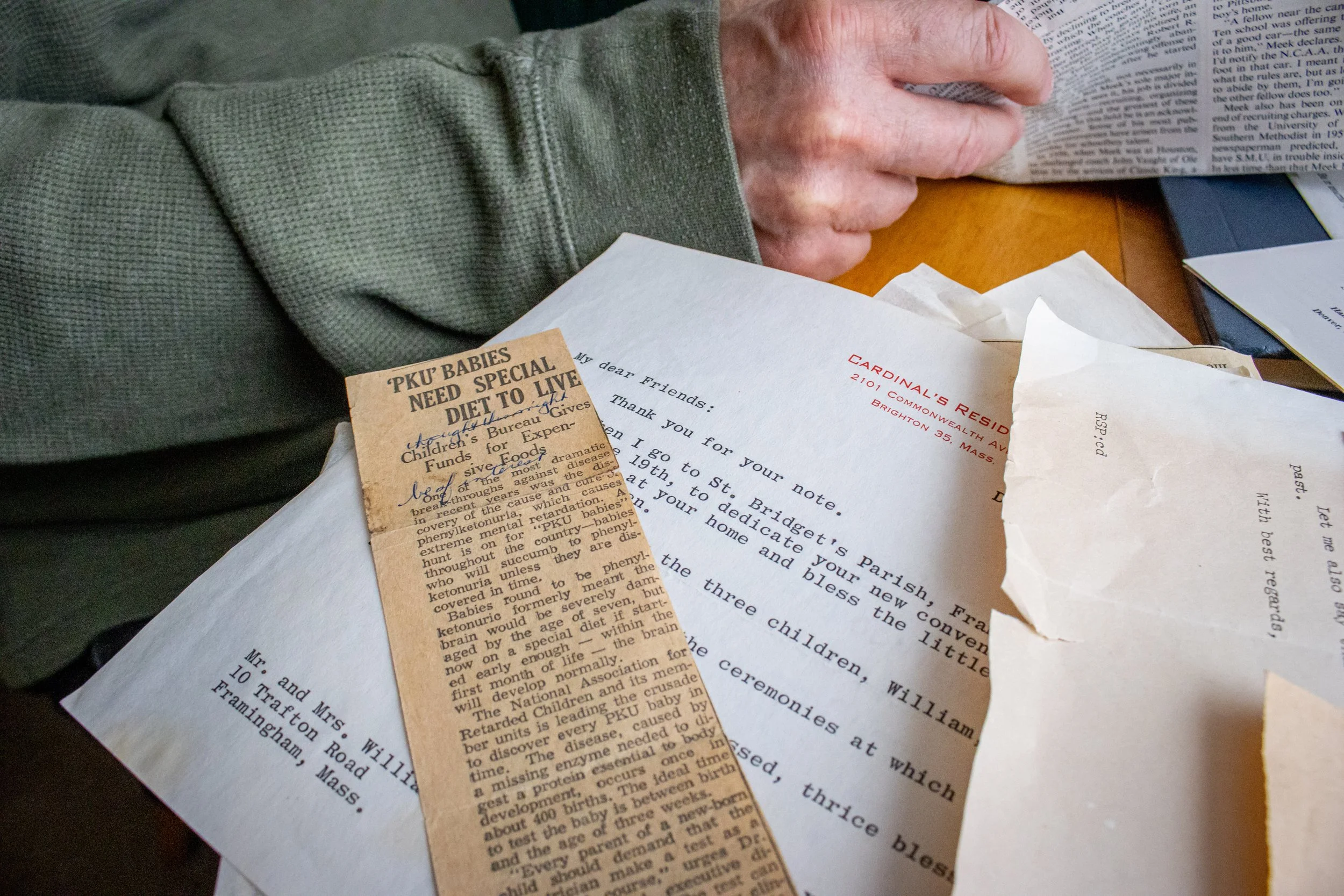

Born in 1953 in Ithaca New York, and growing up in Framingham Massachusetts, Bill Byrne was diagnosed with a rare disease called Phenylketonuria (PKU) soon after he was born, which has fewer than 20,000 cases a year in the U.S. Diagnosed at a very young age, this disease affects the body’s metabolism and breakdown of the amino acid phenylalanine, requiring those suffering to stick to special diets. No chocolate cake, no cheeseburgers, no tuna, or other foods high in protein and dairy. When untreated, the disease can cause intellectual disabilities and seizures, among other issues.

Bill’s mother Emily and father William took him to many doctors, but at the time, in the late 1950s, the disease was not only rare, but rather new, and not much research had been done on it. Many of the doctors couldn’t figure out what was wrong with Bill and kids in that situation were often sent to mental institutions, where good care and basic human rights were in short supply.

At least one doctor suggested institutionalizing Bill, because he would never be able to walk or talk. As he delivered this recommendation, the doctor focused on the window behind the Byrnes. After he finished talking, he pointed outside. Outside a cemetery sits, blindingly white and covered in snow.

Bill’s parents turned around to find a cemetery filling the view.

Bill trailed out of the doctor’s office holding his mother’s hand. Driving down the highway on the way to the next appointment, Bill’s dad makes a U-turn in the middle of the road and starts to drive home. He’s done, he says. They’re not putting Bill in any institutions.

“My mom and dad saved me,” Bill says. “That they had a sense not to put me in an institution. Back then they didn’t have group homes, so they threw a lotta kids in institutions and forgot about them.”

Bill, his younger brother Chris, and his younger sister Eileen, all had PKU. Holding back a few tears, Bill says if it wasn’t for his family, he wouldn’t have made it, and he wouldn’t be the person he is today. He believes family of any kind is vitally important, his father told him and his siblings to always find a support system, no matter where they all end up in life.

Instead of being locked up, Bill broke out. He became the poster child for his disease throughout Massachusetts.

PKU can be treated and cured if it is caught early enough in the baby's life. From here, Bill’s father, William G. Byrne Senior, and his mother Emily, advocated for all babies to be tested for PKU, so that the disease wouldn’t affect the lives of other parents.

PKU can be well treated if caught early on, but when left untreated, it can cause permanent brain damage, intellectual and developmental disabilities, and sometimes seizures.

In 1963, largely thanks to people like Bill’s father and mother advocating, Massachusetts, Bill’s homestate, became the first U.S state to require all babies to be tested for PKU. By 1975, 43 states required testing for PKU.

He was often featured in the Boston Globe, The Boston Traveler, and made special guest appearances on radio stations across the metropolitan area. Before he even hit double digits in age, Bill was telling the public about his disease, and informing the community about other kids suffering from intellectual disabilities.

Despite his micro-celebrity status, Bill still struggled every week with feeling accepted, and being accepted in society. Work was especially difficult.

In the 1970s into the early 80s, Bill helped his childhood best friend Dave Dewar run his lawn care service. Using two push mowers and a Chevy Nova they got from Dave’s father, the two would cut lawns around Morris Plains.

“Dave really believed in me when other people didn’t,” Bill says. “Often I would get people asking Dave ‘what’s that retard boy working with you for?’ as I was standing right there. It really hurt.”

Like many people, when Bill was feeling hurt and let down by the people around him, he used his friends to help him. Bill’s oldest friend Ron Lewis, who he’s known since 1955, was one of those people who always put Bill in a better mood.

Bill, Dave and Ron liked to go bowling, play miniature golf, and go to the movies together in Barrington New Jersey where they lived as young adults. Ron started to laugh as he reminisced decades in the past about bowling with Bill.

“Bill says I set a world record in bowling,” Ron said. “ And that doesn’t really happen a lot.”

Eventually Bill had to leave Dave and Ron behind as his family relocated from Barrington New Jersey, up north to Morris Plains. Bill says moving away from his friends was one of the hardest things in his life.

“Me and him were like brothers,” Bill said. “ When I found out I was moving away from him, I didn’t even tell him until it actually happened, over the years I didn’t talk to him because I was getting adjusted up here.”

While Dave and Ron are his best friends, Bill says the person he is most grateful for is Marry-Ann Kormongy, an old girlfriend of his.

Back when they were young Bill loved taking her to football games in high school so the two could watch his brother play, even though they lost nearly every game.

Kormongy, who is legally deaf, would get bullied growing up and into adulthood for wearing a hearing aid. Bill often stood up for her, and she would for him too.

“She's been very supportive of me since I met her,” Bill said. “When I had a tough life at home, I had a birthday party and some people over, I ran into a situation where I was in a really rought spot, so right away she came over to help me out of that situation.”

Kormongy and Bill dated for a long time, but in the end things didn’t work out. Kormongy was receiving pressure from her family to break up with Bill, due to him not being able to financially support a family. The two split. She is now happily married to her husband Phil, but Bill says she still remains as a pillar of support in his life.

“Even though we’re not together anymore, she is still my rock, and a very supportive person in my life. Even though Phil is married, Phil is just as supportive and I'm grateful for them.”

-

At 36 in 1989, Bill was elected president of the United Self Advocates of New Jersey, or the Unity Club, a group that advocated for the rights of those with disabilities.

He received a congratulatory letter from Justin Dart, who was the chairperson of the Task Force on the Rights and Empowerment of Americans with Disabilities at the time. The letter informed Bill about the rough draft of The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

"I played alotta sports as a kid, baseball was one of them,'' Bill said. “One time this kid made fun of me during gym class at Paul Six High School in Haddon Township, New Jersey, saying I couldn't hit the ball, so I had him pitch to me,” Bill laughs. “I hit the ball so hard, it bounced right out of his glove, I screamed ha! There ya go, now you can't say retarted people can’t hit."

Two years later, Bill had won first place in the TK event at the International Summer Special Olympics, taking home a heavy gold medal. In fact, in his lifetime, Bill has won over 70 Special Olympic medals. As Bill got older, he started doing race walking, which was less hard on his knees. To continue to help, Bill began coaching race walking as well as bowling in the Special Olympics.

During the early 1990s when disability advocacy got heated because of the introduction of the ADA, Bill decided to take a break from the Special Olympics to focus more on advocating for those with intellectual disabilities.

Now at 69 years old, living in Morristown, New Jersey, Bill spends a portion of his free time standing at nearly every corner around town, waving a sign the same size as him that reads “PEOPLE WITH INTELLECTUAL DISABILITIES MATTER,” while wearing a pin that tells people not to use the “r-word.”

“I carry that thing with me everywhere,” Bill says. “I was up on the Morris Green, I was going up Franklin Street, one guy goes up to me and says God bless you sir. I’m on Facebook, I mean people go nuts.” Throughout his life, he’s never let his disability slow him down.

When Bill carries his sign around town he holds it up to any school bus that passes by in hopes that the younger generation will take note. Some people in passing try to offer Bill money, but he always turns it down.

"I'm not soliciting, I'm educating, if I take money, things get messy.”

For the past 40 years Bill has been an active member of the ARC, formerly called Association for Retarded Citizens of the United States, giving speeches across the country, from New Jersey, to Alabama, Alaska, and Toronto.

Members of the community along with Bill were strong advocates for removing the r-word from the ARC name, as they found it both offensive and demeaning to what Bill calls “his fellow brothers and sisters.”

Salvador Moran, the executive director, and CEO of the ARC of Morris, as well as Bill's old friend, says he has done work for the ARC for many years.

“ARC Morris has known Billy for over 40 years, he is a strong advocate for people with disabilities because he is in a position where he thinks he can help them from an advocacy perspective.”

In Morristown, Bill attends every council meeting. During the public hearing portion, the town council always expects Bill to say something, even if all the other pews in the town hall are empty, with no one else there to listen.

Lately, Bill has been advocating for an increase in wages for direct care staff who help the people with intellectual disabilities, among a new state budget. Over the years Bill has turned an acquaintanceship into a friendship with Morristown Mayor Timothy Dougherty.

In 2012, Mayor Dougherty presented Bill with a Proclamation, officially naming August 16th Bill Byrne day in Morristown.

Two years later in 2014, Mayor Dougherty presented Bill with the Key to the City of Morristown for his disability advocacy and involvement with the 31st annual Self-Advocacy Conference, where he gave a speech and presentation titled ‘Person Centered Language-Speaking with Respect.’

“Bill and I have a genuine friendship, which I truly cherish.” Dougherty said. “He means a lot to me personally and to many within the Morristown Community. We often have lunches, dinners and coffee together. I am so proud of his self-advocacy accomplishments in helping people with intellectual and developmental disabilities and for his work in the community.”

As each day passes Bill can’t help but worry more and more about his future, and about the next generation of disability advocates. “I don’t got much time left,” Bill says as he looks through all the old photos of him and his friends.

Along with direct care staff wages and state dollars being put towards those living in disability group homes, Bill has been advocating with Mayor Dougherty over people riding bicycles on the sidewalks around Morristown.

Many people suffering from intellectual disabilities in Bill’s generation were strong advocates in fighting for their human rights and inclusion in society. But now that mental institutions are closed, and the r-word is seen as demeaning, being used less and less, Bill fears many people will get comfortable, and stop advocating for the things his generation fought dearly for.

“Don’t take your services or your right to vote for granted,” Bill says. Legislation like The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and other anti-discriminatory laws that give him and his brothers and sisters rights. Despite these laws Bill still feels like there is a lot of work to be done in terms of budgeting and financing for those with disabilities.

“We’re at war right now,” Bill says. “This is a war about living out in the community, it’s about having a job, it’s about your life.”

While many senators and governors across the country are supportive of those with physical and intellectual disabilities, he fears the world will one day forget about those with intellectual disabilities, and vote in officials who don't care for people like Bill.

To jog his memory, Bill lays out nearly all his old photos, dating back to before his earliest memories in the early 50s, to just last month, the memories flooding back put a smile on his face, but also a tear.

“Just believe in yourself and know that you can do anything you put your mind to, don’t let anyone tell you differently.”

-

Even as he approaches 70 years old, Bill tries to stay as active in his community as he can.

In September of 2022 he was nominated and awarded the Colleen Fraser Self-Advocate Award by the New Jersey Council on Developmental Disabilities for his years of advocacy.

William Testa, who served as the Morris ARC's Executive Director for 29 years, praised Bill on his continual fight for those with intellectual disabilities during a ceremony for the Colleen Fraser Self-Advocate Award.

“Bill Byrne has been a tireless disability advocate for Morris County for nearly 40 years,” Testa said. “He continues to be extremely active on the local level, being on a pedestrian safety task force, as well as numerous housing committees, he is always working hard to recruit new self-advocates, who he hopes will continue his legacy.”

While in retirement, Bill manages nine different housing committees for the ARC of Morris. He is on a rent level board for Morristown, but worries about the direct care staff that help care for those with intellectual disabilities.

“The morality is really down,” Bill says. “Some of them may leave soon, it's getting so bad. They don't need 15 dollars an hour, they don't need 14 dollars, they need like 20 dollars or 24 dollars an hour to get them to stay. A lot of them don't just take care of us, they deal with many different issues and other people.”

Bill has also helped others with intellectual disabilities get into self-advocacy, such as his friend Kevin White, who spent many years participating in the Special Olympics with him. White has also gone to national ARC conferences with Bill, and Bill serves as his mentor

Every October, the Morris County ARC hosts a walkathon to help raise money for those with intellectual disabilities. To help even more, Bill went door to door to businesses around Morristown to try and help raise money for the ARC.

While the ARC of Morris raised over $20,000 for their 2022 walkathon according to Robert Fontana, the Personal Executive Assistant for the ARC, Bill managed to single handedly raise $400 by himself to help his friends who may be suffering from their disability.

Bill said if he got to live his life over again, he wouldn’t change anything about himself.

“As you get older, and you see the difference that you're making, you know, it’s like for anything in the world, I wouldn't change this, because having a disability is not a bad thing, I can use it to educate people in a disability community, and teach them that this is just what it's like.”